Sidney H. Kennedy, MD, FRCPC, FCAHS

Department of Psychiatry, Krembil Research Centre,

University Health Network, University of Toronto

Centre for Depression and Suicide Studies,

St. Michael’s Hospital,

Keenan Research Centre for Biomedical Science,

Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute,

St. Michael’s Hospital

Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto

Trehani M. Fonseka, MSc

Department of Psychiatry, Krembil Research Centre,

University Health Network, University of Toronto

Department of Psychiatry, St. Michael’s Hospital,

University of Toronto

Background

In 2013, major depressive disorder (MDD) was identified as the second leading contributor to global disease burden, according to disability-adjusted life years, in developed and developing countries.1 By then, previous optimism about antidepressant efficacy had been challenged by results from the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) trial, showing that less than 30% of individuals achieve remission after the first monitored antidepressant treatment trial.2 While depression guidelines serve a useful purpose in translating evidence into clinical recommendations for optimal use of existing treatments, they require updating especially when a landmark trial is published.

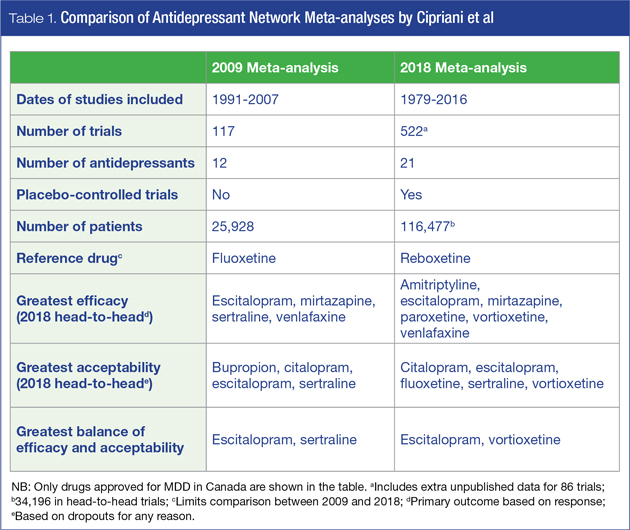

Such a landmark publication occurred in February 2018 when Andrea Cipriani et al from the University of Oxford published a multiple-treatments (network) meta-analysis comparing the efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressants for the acute treatment of (unipolar) MDD in adults.3 This publication followed a previous multiple-treatments meta-analysis by the same authors comparing 12 antidepressants.4

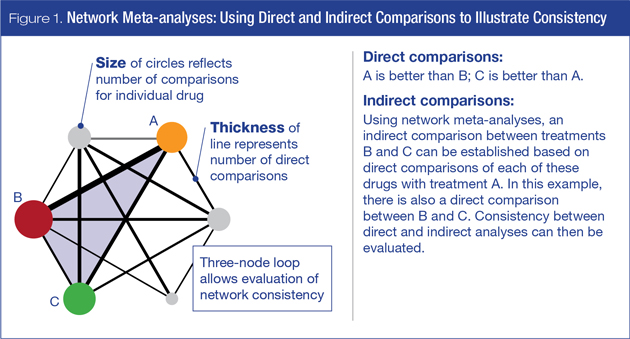

Network meta-analyses allow direct and indirect comparisons across a wide range of treatments. Figure 1 illustrates direct and indirect analyses, and also provides a measure of consistency in this three-node loop. This technique has been widely used in areas of medicine such as comparison of statins to prevent cardiovascular (CV) mortality5 or the impact of smoking cessation therapies on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).6

Methods

The aim of this review is to present highlights of the new network meta-analysis and provide an interpretation from a Canadian perspective to simplify the therapeutic decision-making process for physicians.

This comprehensive network meta-analysis is by far the largest compilation of published and unpublished antidepressant clinical trials involving placebo-controlled and head-to-head comparisons. Data were extracted from 522 double-blind trials (58% placebo-controlled) published between 1979 and 2016, including 86 trials that were retrieved from unpublished records. The number of trials for each antidepressant varied considerably: fluoxetine and paroxetine each contributed more than 100 trials, while milnacipran, desvenlafaxine, vilazodone, and levomilnacipran each had 10 or less. It should be noted from a Canadian perspective that several antidepressants included in the analysis are not approved for the management of MDD in Canada: agomelatine, milnacipran, and reboxetine are not approved, while the sale of nefazodone was discontinued in Canada in 2003.

There were almost 117,000 patients in total, with more than 34,000 in the subset of head-to-head comparisons. All second-generation antidepressants approved by at least one of three regulatory agencies (U.S., European or Japanese), together with two World Health Organization (WHO) essential medications (amitriptyline and clomipramine) were included. Only trials within the approved therapeutic dose range (n = 474) were included in the final analyses, and only short-term (8-week) outcomes were assessed. Not only is this a much larger trial than the previous meta-analysis of new-generation antidepressants,4 which included almost 26,000 participants from 117 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), but the addition of placebo-controlled RCTs also allows definitive analysis of antidepressant efficacy.4

The two primary endpoints of this particular network meta-analysis were efficacy and acceptability. Efficacy was defined as “response rate,” measured by the total number of patients who had a ≥ 50% reduction from baseline on either the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) or Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). Acceptability reflects treatment discontinuation, measured by the proportion of patients who withdrew for any reason. Secondary outcomes were the endpoint depression score, remission rate, and proportion of patients who dropped out early due to adverse events (AEs).

Results: Efficacy and Acceptability

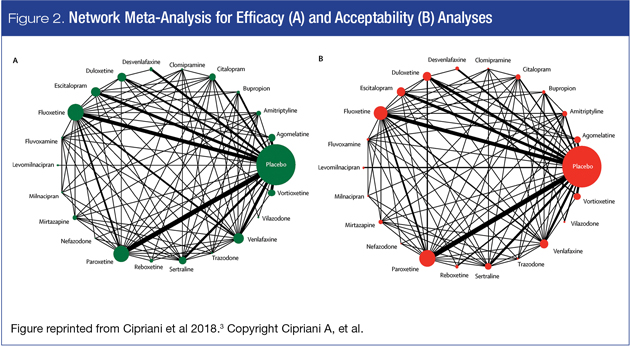

Efficacy and acceptability are demonstrated in Figures 2A and 2B, respectively. Since the pathways illustrated in both network plots are almost identical, this increases confidence that the same subjects and trials are represented in the analyses.

Note that while all the studied medications are shown in these pathway diagrams, the summary and interpretation of the data presented in the sections below include only the medications approved in Canada for the treatment of MDD.

Analyses vs. placebo. The main efficacy finding was that all 21 antidepressants are superior to placebo (432 trials), with amitriptyline at the top and reboxetine at the bottom, and with modest differences between antidepressants in terms of odds ratios. This prompted newspaper headlines such as “The drugs do work: antidepressants are effective.”7.

In terms of acceptability, fluoxetine emerged as superior to placebo, while clomipramine was worse.

Head-to-head analyses. Relative to the placebo-controlled analyses, drug-drug differences were amplified when only head-to-head studies were examined. Among 194 studies with at least two active groups at licensed dose (N = 34,196), amitriptyline, escitalopram, mirtazapine, paroxetine, venlafaxine and vortioxetine were more effective than other antidepressants; while fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, reboxetine and trazodone were among the least efficacious drugs.

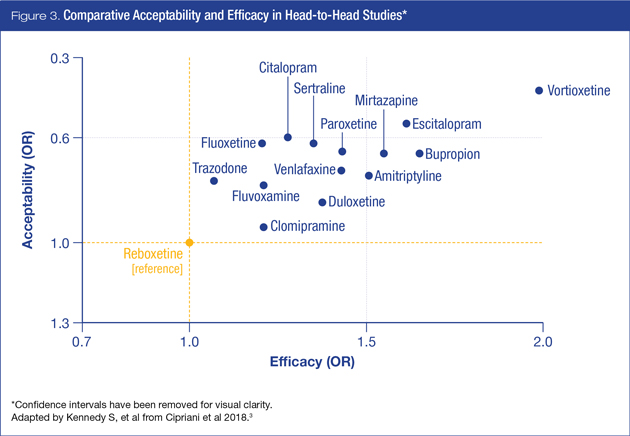

Figure 3 illustrates the relative balance between efficacy and acceptability in comparison to reboxetine, among agents available in Canada.

In the head-to-head acceptability analysis, among agents available in Canada, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline and vortioxetine were found to be more acceptable than other antidepressants, while amitriptyline, clomipramine, duloxetine, fluvoxamine reboxetine, trazodone and venlafaxine were associated with the highest dropout rates.

Since clinicians generally select antidepressants on the basis of efficacy and tolerability, integration of efficacy and acceptability data is of particular benefit. In this case, vortioxetine and escitalopram appear to have the most favourable profiles of the agents available to Canadian clinicians and their patients (Table 1).

Implications for Clinical Practice

While many cautions have been raised about quality control and interpretation of systematic reviews and meta-analyses,8 the same author has also proposed standards to mitigate against reporting biases.9 Cipriani et al took six years to complete this project, and have addressed issues pertaining to credibility, validity, and applicability of their findings. Nevertheless, the following limitations are acknowledged: 1) data were less complete for older antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline and clomipramine) compared to more recent antidepressants (e.g., agomelatine and vortioxetine); 2) the number of trials included for each drug varied considerably (e.g., 117 with fluoxetine compared to six with levomilnacipran); 3) the majority of trials exclusively recruited outpatients (77%), while the remainder included inpatients and outpatients; 4) only short-term (8-week) outcomes were assessed; 5) functional outcome measures were not included; and 6) while the authors went to considerable lengths to identify unpublished trials, they could not guarantee that all were found. Most significantly, the compromise in working with a large dataset is the lack of individual response outcomes. Given the heterogeneous nature of MDD, it is important to consider potential subgroups within the larger dataset where excellent responses as well as non-response co-exist. The combination of aggregate data through network meta-analyses precludes investigations at the individual patient level, which includes examination of individual treatment-response trajectories and measures of side-effect variability.10

Nevertheless, the outcomes from this meta-analysis have significant translational implications for clinical practice, where antidepressants with the highest ratings of efficacy and acceptability should be considered as first-line options for the treatment of MDD. Moreover, the superiority of all antidepressants over placebo should put to rest previous doubts about their efficacy, despite high placebo response rates and wide inter-patient variation.

References:

1. Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015; 386(9995):743-800.

2. Gaynes BN, Warden D, Trivedi MH, et al. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv 2009; 60(11):1439-45.

3. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018; 391(10128):1357-66.

4. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 2009; 373(9665):746-58.

5. Zhong P, Wu D, Ye X, et al. Secondary prevention of major cerebrovascular events with seven different statins: a multi-treatment meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017; 11:2517-26.

6. Strassmann R, Bausch B, Spaar A, et al. Smoking cessation interventions in COPD: a network meta-analysis of randomised trials. Eur Respir J 2009; 34(3):634-40.

7. Boseley S. The drugs do work: antidepressants are effective, study shows. The Guardian 2018; 21 February.

8. Ioannidis, JP. The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q 2016; 94(3):485-514.

9. Ioannidis, JP. Meta-analyses can be credible and useful: a new standard. JAMA Psychiatry 2017; 74(4):311-12.

10. Parikh SV, Kennedy SH. More data, more answers: picking the optimal antidepressant. Lancet 2018; 391(10128):1333-4.

Development of this article was made possible through the financial support of Lundbeck Canada Inc. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Lundbeck Canada Inc. The authors had complete editorial independence in the development of this article and are responsible for its accuracy. The sponsor exerted no influence in the selection of content or material published.